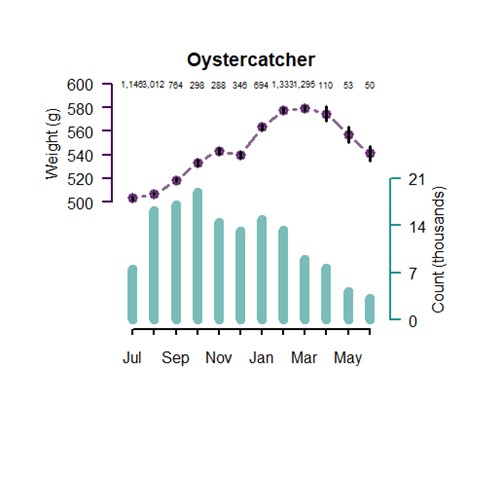

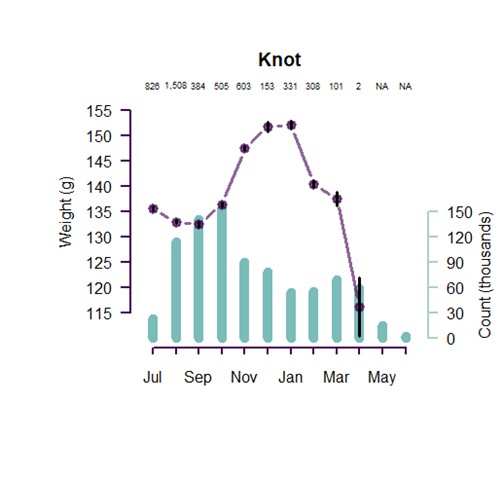

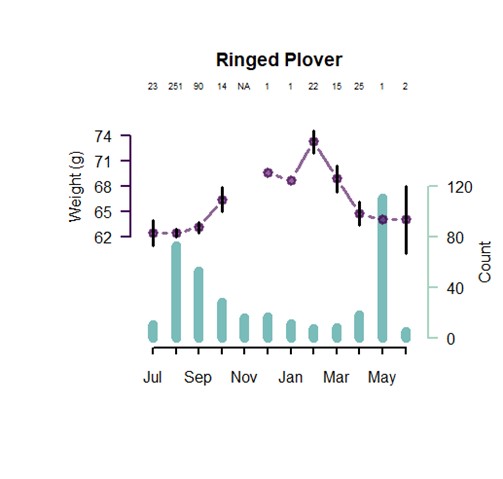

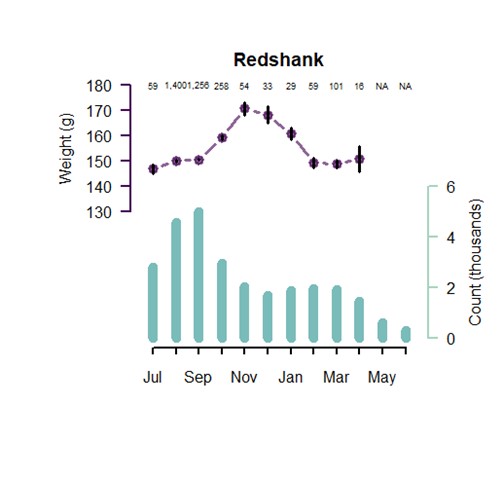

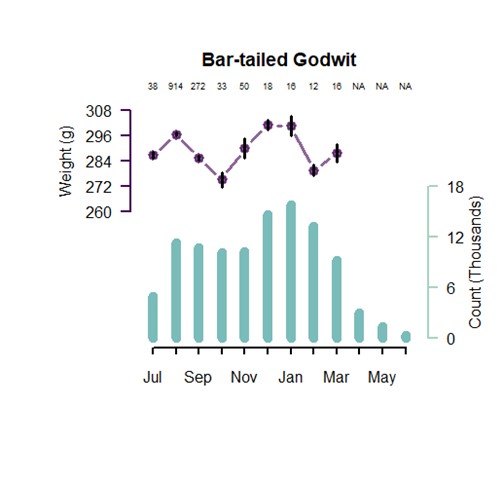

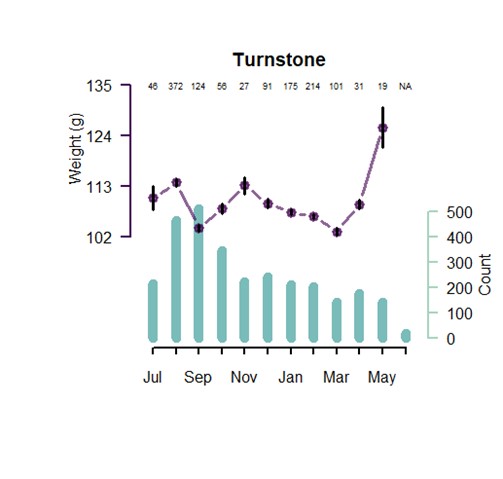

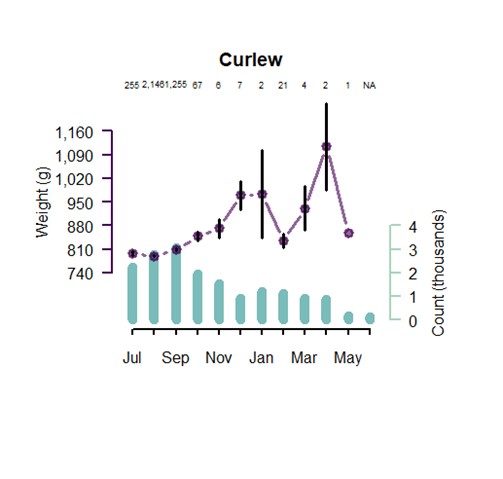

Waders change weight through the year in a predictable pattern, depending on the need to increase weight for migration or for ‘insurance’ against unusually severe weather when feeding might be restricted. They probably keep their weight as low as possible for the time of year as both gaining and carrying extra weight has risks – more time spent feeding can expose birds to increased predation risk and extra weight may affect their manoeuvrability and therefore their ability to escape predators. The typical weight pattern is explained below.

Autumn

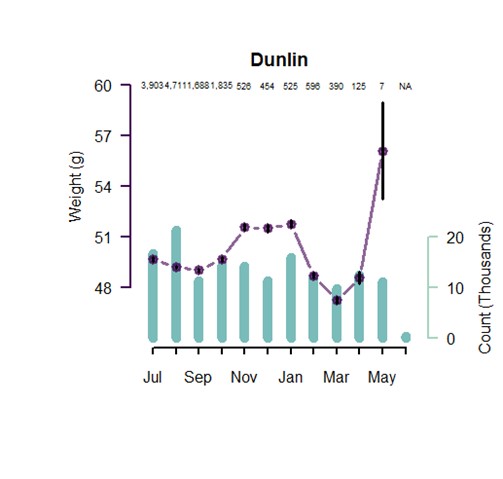

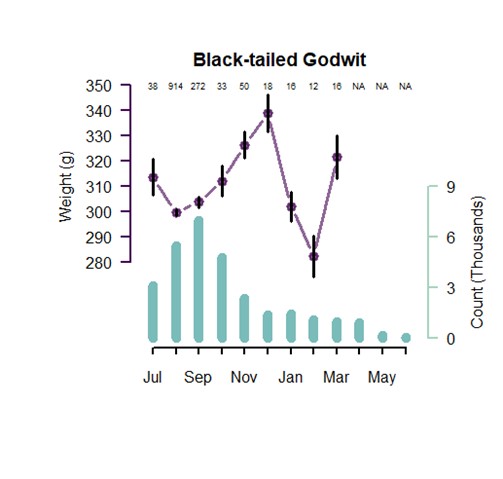

During moult, adults maintain a relatively constant weight which is generally only slightly over fat-free weight. Although moult in waders is progressive, with only a small number of primary feathers dropped or growing at one time, the birds’ manoeuvrability and ability to fly long distances decreases due to the reduced wing area. At the same time, their energy requirements probably increase as new feathers grow. Waders therefore tend to congregate to moult on large estuaries, such as The Wash, which are rich in food and have relatively low numbers of predators.

Non-moulting adult waders on The Wash in autumn are usually staging during their migration to wintering grounds further south or west. They generally stay for a short time, gaining weight rapidly to fuel their onward migration.

Juvenile birds arriving on The Wash for their first autumn are lighter than arriving adults. By October, the mean weight of juveniles is closer to that of adults, and it generally remains that way for the winter.

Winter

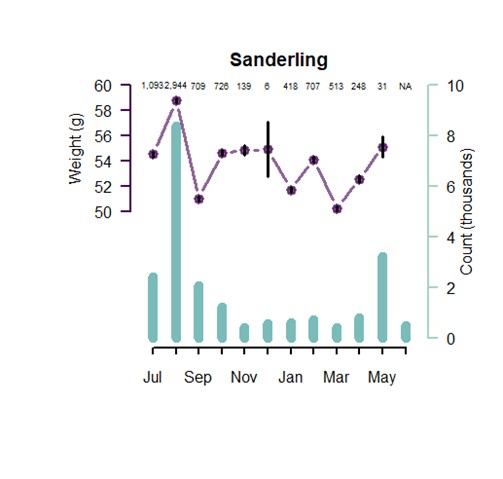

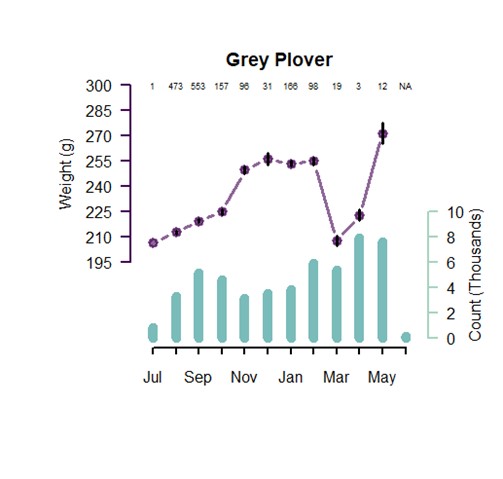

After moult, waders start to put on weight, reaching a peak in late December/early January, after which weights fall until they are close to fat-free weight in March. The early winter increase in weight is ‘insurance’ to potentially mitigate the effects of unusually severe winter when energetic requirements are high due to cold and/or wind and feeding may be limited.

Although waders feed at night, it is likely that they are more successful in daylight, so the short days of mid-winter may limit their feeding capacity. In addition, prey may bury deeper in cold weather and become inaccessible, ice may make it difficult or impossible to feed in the intertidal area and wind buffeting birds may make it more difficult to feed. Carrying fat in unusually severe weather enables waders to survive without sufficient daily food resources or, for some species, to have the energy to allow them to move south and west to a warmer area. Falling weights after mid-winter likely represent a strategy to maintain as low a weight as is necessary, given the relative day length and chances of cold weather, rather than a necessity.

Spring

Adult waders put on weight between March and May, reaching the highest level in the weight cycle as they build-up energy reserves for migration to breeding areas. For some species, this will provide enough ‘fuel’ for them to reach the breeding grounds, while others will stage elsewhere. The weight increase may provide a little more fuel than the birds need for their journey. This means that in a late season, when there is still snow cover when they arrive on their breeding grounds and feeding is impossible, they are able to survive until the snow clears and allows them to feed.

Juveniles do not tend to put on weight in spring as many will not breed in their first year and may either summer on The Wash, or only migrate part of the way to the breeding grounds.

Weights of waders caught on the Wash by WWRG members and WeBS* counts of the number of each species on the Wash by month. Weights are the monthly means for adults only and include all data currently computerised. Sample sizes are at the top of each graph. The graphs run from July, when birds arrive back from the breeding grounds, to June, by which time most adults have left.

*Data provided by the British Trust for Ornithology on behalf of The Wetland Bird Survey. The Wetland Bird Survey is a partnership jointly funded by the British Trust for Ornithology, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, in association with the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, with fieldwork conducted by volunteers.