The Wash is one of the world’s most important sites for waders, particularly during the autumn passage period when many tens of thousands of birds use it as a ‘service station’ on their southward migration. Members of Cambridge Bird Club (CBC) had been monitoring and counting waders on The Wash for several years and had caught small numbers using mist nets and clap nets. However, when Peter Scott developed a new method of catching large numbers of wildfowl – rocket nets, this offered an ideal opportunity to catch good numbers of roosting waders in order to learn more about their incredible journeys. The Wash Wader Ringing Group was formed in the summer of 1959, when members of the CBC, including Clive Minton, WWRG’s first leader, borrowed some nets from the Wildfowl Trust (now the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust), and embarked on a week-long period of fieldwork.

Only one net was ‘fired’ that summer, but 1,132 birds were caught, three of which were Dunlin that had previously been ringed elsewhere; one in Lincolnshire 18 months previously, one in Finland the previous year and a Danish-ringed bird caught a month before it was encountered on The Wash. The rocket nets were used during a further six weeks of fieldwork between 1960 and 1963. In total, 12,916 new waders were ringed and several hundred more were retrapped or controlled. Prior to the development of rocket-netting, and later cannon-netting, as a technique for catching large numbers of birds, few waders had been caught in Britain & Ireland, so these birds helped greatly in the understanding of ageing and sexing techniques, moult strategies and migration routes.

The 1960s

During the first two years of fieldwork, accommodation was a borrowed caravan, but from 1961 the Group was based at a house at Wisbech Sewage Farm that belonged to the Cambridge Bird Club. Another early base for the group was a potato chitting shed, essentially a large greenhouse, at Holbeach St Mark.

After 1963 the cordite used to fire the rocket nets became scarce and new methods were required. In rocket nets, the projectile attached to the net is slotted over the launching mechanism. Cannon-nets, in which the projectile is slotted into a launching tube, are more efficient as the rapid expansion of air within the tube provides extra power, meaning less powder needs to be used. In 1966, members of the Ministry of Agriculture, who had started using cannon nets for catching Oystercatchers in western Britain, were persuaded to bring eight small cannon nets to The Wash. Although they were successfully used on two occasions to catch Dunlin, they weren’t quite what was required, so in 1967 the group developed and manufactured its own cannon-netting equipment, using it for the first time in July 1967. The cannon-netting equipment used today is similar to that developed in the 1960s, albeit with a few alterations. Once the Group had its own canon-netting equipment they were able to expand their area of operations and start using new catching sites: in 1967 the beaches at Heacham and Snettisham, and the fields on the east Wash, came into use.

In 1967 the Group’s base was a large, open ended, semicircular, tin-roofed shed full of (mostly vacant) pigsties on the east Wash, where each member (or family) was allocated their own sty! The Group then moved to a more spacious barn at Dersingham and then to an old granary in Snettisham, which just happened to be next to a pub.

By 1968 catching activities were taking place in most months of the year, rather than just during the summer months, and approximately 10% of the birds caught that year were already carrying rings. In order ‘to maximise the Group’s work on The Wash‘, they also began cannon netting elsewhere in the UK, including Morecambe Bay, Piel and Walney Islands in Lancashire.

Beginning in 1969 the group significantly changed its catching tactics and started deliberately aiming for samples of specific species to fill knowledge gaps on weight, moult and biometrics, a strategy still employed today. The group also ringed its 10,000th Knot that year; by now 20% of the birds being caught were already ringed, that figure rising to 60% and 45% respectively for Turnstone and Sanderling. Knowing the history of so many individuals helped form our understanding of wader ‘flyways’ that now underpin conservation efforts around the globe.

The Group’s first ‘Purpose Statement’ was defined in 1969. The statement outlines the importance of The Wash as a major wintering area, a major staging post on migration, and a major moulting area. It noted the impact that any change in the status of The Wash could have on the birds using it and stated that ‘it is our intention to discover, as fully as possible, all aspects of the behaviour of the waders which visit The Wash for these various purposes so that if, and when, any decision has to be made on altering its nature (e.g. by building a barrage) the data already exist on the largest group of fauna which use this unique habitat. This data can then be used to make judgements of the consequences of any proposed course of action’.

As intimated in this statement, part of the motivation of the Group in these early years were mooted plans to build a tidal barrage across half of The Wash which would capture water from the Rivers Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse to form a large reservoir to provide water for the rapidly growing human population. Fieldwork undertaken by the Group provided information to the Wash Feasibility Study, undertaken by the Water Resources Board, and provided a major contribution to the assessment of the present knowledge of waders on The Wash and the predictions of the effects of the proposed water storage reservoirs. Although the project was shelved as the enormous impacts and costs became clear, the two ‘trial’ banks, constructed as part of the feasibility study, can still be seen today; the outer one now home to a nationally important gull colony.

The 1970s

In 1970, the Group ringed it’s 50,000th bird. Mist netting at Terrington, on the south side of The Wash, began in 1971. In the early 1970s, the Group attempted to fill in existing gaps in biometric data by taking measurements, including weight and moult state, for 100 adults and 100 juveniles of every population of every species for every month of the year. Knot caught during catches in March 1971 and March 1972 were subsequently reported in Barbados in the West Indies and Baffin Island in Canada five and three months later respectively; remarkably the bird recovered in Canada had been ‘killed with sling shot by Eskimo child‘. Additionally, 67 Knot ringed on The Wash were recovered during an expedition to Iceland whilst a further 21 were reported from Greenland, and 47 Knot ringed on the Dee / Morecambe Bay were controlled on The Wash. In addition, nine Knot from The Wash were controlled on Irish sea coasts. These data were helping to build a picture of the migration strategies of the waders using The Wash.

The early to mid 1970s saw important catching developments such as the invention of the jiggler (see the Glossary for explanation of terms used), reusable cartridges (and the use of plasticine instead of candle wax (!) to seal the cartridges) and the use of decoys. In 1973, the Group started operating two separate teams during summer fieldwork trips, one in Lincolnshire and the other in Norfolk.

In 1978 Clive Minton, the Group’s leader, left to work in Australia for a few years and the Group’s base moved to buildings associated with an old flax factory in West Newton on the Royal Estate at Sandringham. This year also saw the introduction of metal bar projectiles to replace the original rope projectiles that frequently broke. By 1982, Clive had decided to stay in Australia and Phil Ireland took over as Group leader from 1 January 1983. Phil remains Group Leader and Clive Honorary President of the Group to this day; without their drive and enthusiasm the Group would surely have been much less successful .

The 1980s

In the late 1970s / early 80s the Group began preparing processing data for entry onto a then state-of-the-art computer-based data storage system, introduced under the auspices of the BTO’s Wader Study Group. This involved developing a new processing sheet for recording data in the field and transcribing all previously acquired processing data onto the new forms – a tedious job indeed. By the mid- to late-1980s, ringing and retrap data were routinely entered onto the computer, while biometric data were entered commercially. As time passes so technology moves on, and several group members are now engaged in a mammoth task of sorting and tidying these data to ensure they are available for the sophisticated analyses that can now be undertaken. The Group’s unparalleled historical archive of measurements provides an invaluable baseline against which to judge the changes we see today and which are likely to continue into the future.

In 1989 the Group developed its first formal statement of its aims. This aim basically remains the same today and can be found on the What we do page.

The 1990s

We are used, nowadays, to relatively mild winters and snow and frost are increasingly uncommon on the Wash. In the past though, extremely low temperatures would persist for days on end, providing a real challenge to the birds using The Wash. In February 1991, as a result of extreme cold weather when the average daily temperature remained below zero for nearly a fortnight, the Group made an additional visit to The Wash to collect wader weight data. Birds caught at the beginning and the end of the month demonstrated a significant fall in weight as birds had reduced feeding and used up their body reserves simply to keep warm. Whilst twinkling for a catch, a team member found a number of dead birds on the tideline. Dedicated walks along the tideline to search for additional corpses discovered nearly 3,000 dead waders, 2,500 of which were collected to study the effects of severe weather. The vast majority of the dead birds were Redshank, but Grey Plover and Dunlin were also found in considerable numbers. Approximately two-thirds of the wintering Redshank population on The Wash died during this cold spell. The long-term datasets held by the group provided the background information to fully understand the impact of this mortality event.

The winter of 1992/93 saw dozens of dead Oystercatchers washed ashore. Additional fieldwork in 1993 to catch Oystercatchers showed that several were very light and many had failed to complete their autumn wing moult, suggesting they were struggling to find food. The Group continued to catch Oystercatchers on a regular basis through the mid 1990s to build up information on how they were responding to continued pressure on their food supply (shellfish). Analysis of the catching data showed that body condition of birds in autumn is related to the state of the shellfish stocks and that subsequent winter mortality is linked to autumn body condition. Low cockle and mussel stocks in The Wash during the early 1990s led to 30,000 birds (75% of the population) being lost from The Wash population. The Group’s work has helped ensure the management of the shellfisheries in The Wash are more sustainable.

In 1993 the group started colour ringing Black-tailed Godwits as part of a larger long-term study in which the migration, habitat use and behaviour of individual birds was tracked. This study involves a network of observers in the UK, Ireland, France, Portugal, the Netherlands and Iceland tracking birds along their migration routes, and between years. The project is still ongoing and now encompasses nearly a dozen countries.

By 1994, the data collected by the Group had been published in 79 papers on topics ranging from biometric data to migration studies to cannon-net construction. Today, that number has increased to c. 110. A list of key publications that have used WWRG data can be found on the Scientific Papers page.

In 1997, members of the Group were invited to join an international effort to understand more about the population status of migrant waders. Group members travelled to Delaware Bay, in eastern USA, a key staging area for waders (or shorebirds, as they are known over there!) on their migration from their wintering grounds in South America to their breeding grounds in the Arctic. Concern about the fall in Horseshoe Crab numbers, the eggs of which are the waders’ main food source at this location, prompted local scientists to begin an intensive fieldwork study (now the Delaware Shorebird Project) on the wader populations using the Bay. As local bird ringers have little opportunity to gain experience in cannon-netting techniques, members of the Group were invited to assist with the fieldwork and provide training to local volunteers on the Delaware side of the Bay. A sister project is also carried out on the New Jersey side of the Bay, with assistance from Clive Minton. This project has been carried out annually since 1997, with members of the Group assisting with the fieldwork and training each year, and is just one example of how the Group’s influence has expanded well beyond the Wash to help wader conservation globally.

The 2000s

The group started catching at a new location in 2000, Port Sutton Bridge. Catching here involved cannon-netting on brick weave, helped by the use of 25 sandbags! The target species at this location was Turnstone, which were colour-marked to ascertain whether the populations were using this man-made environment as it was a more profitable food source, or whether the intertidal food supplies had declined, resulting in the port being used as a supplementary food supply. The colour ringing study was extended to the remainder of The Wash in the early 2000s in order to gain a better understanding of the within Wash movements of the species.

The first Wash Wader Ringing Group website was developed in the early 2000s. Although the website has inevitably evolved over the intervening years, it continues to be a portal to attract new Group members, provide information to interested parties and keep current members better informed of our activities, the latter primarily through the blog.

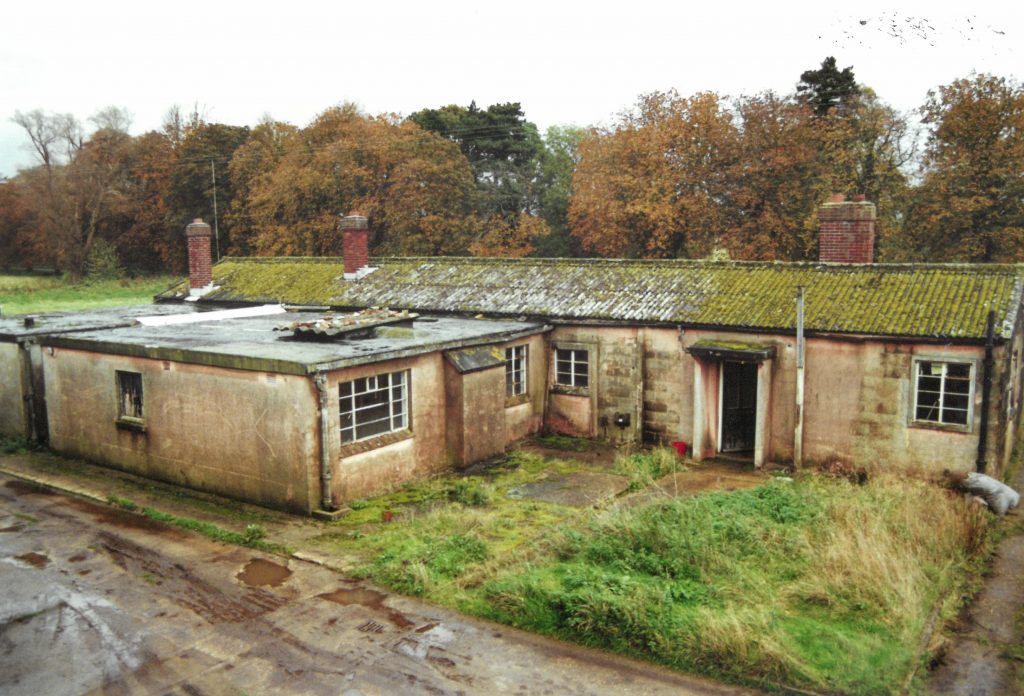

In 2001 the Group vacated the base it had used at West Newton since 1978, ready for the building complex to be demolished, which it was by the end of that year, and re-developed. The Royal Estate kindly made a stable available to use as a store for the Group’s equipment. This year also saw the first visit by the Group to the Outer Trial Bank to catch and ring gull chicks at the request of what was then English Nature (now Natural England – NE). The Group continued to catch gulls and monitor the growth of the colony on the Outer Trial Bank for NE until 2015.

In 2002 the group acquired new accommodation near Terrington in Norfolk. This property, containing showers, cooking facilities and beds was luxurious compared to the barns and pig sheds the Group had used over the previous 40+ years. This property is still the Group’s Norfolk base. By 2005, the Lincolnshire team was hiring Friskney Village Hall as their base for summer catching trips, a habit that persists to the present day.

In 2003 a new landmark appeared on the Terrington saltmarsh; a Sperm Whale that had beached and subsequently died. The remains of its skeleton can still be seen on the marsh. This year also saw the start of a collaboration between the Wash Wader Ringing Group and the Farlington Ringing Group (based around The Solent). WWRG began colour-ringing Greenshank as part of a study looking at movement patterns and migration strategies, instigated by the Farlington Ringing Group in 1992. One bird, colour-marked in Lincolnshire in August 2015, provided the most-northerly record of a BTO-ringed Greenshank when it was seen in Tromsø, Norway, in May 2016.

By 2006 the Group was using small mesh cannon nets. The smaller mesh meant that birds could be extracted from under it much more quickly than from the traditionally-used large mesh nets. This in turn allowed the Group to catch in sites that could not otherwise have been used.

During the winter of 2009 the group undertook a short project on the use of geolocators on Sanderling. The study was carried out at the request of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Recovery Team, who were considering using geolocators on this highly endangered species but wanted to test their use and value on a wader of similar size first. Unfortunately the Sanderling recaught a year after tagging had lost their geolocators; however, after trials involving captive Dunlin, Spoon-billed Sandpipers have successfully carried glue-mounted tags.

During 2010 and 2011, WWRG began colour marking Grey Plover, Bar-tailed Godwit and Curlew to increase the frequency of recording marked individuals through resighting, rather than relying on traditional recaptures. In the case of Bar-tailed Godwit, this project has already increased the re-encounter rate from 1% (for metal ringed birds) to 30%, generating very valuable data on survival rates. See the Current Projects page for more information on the Group’s colour-marking projects.

The first 20 years of the Group saw the biggest changes (and the steepest learning curve) in terms of catching equipment and techniques, as well as increasing our knowledge of ageing and sexing waders, but the data collected today continue to inform our knowledge of moult strategies, migration routes, stopover locations and the way birds are adapting to changing climate and habitats and are of equal importance. Although not at the pace of the first 20 years, the Group is continually developing equipment and improving catching techniques; more recent developments include the use of keeping boxes, silicon sealant for cartridges (which prevents the black powder from getting damp) and the use of jiggler eyes.

Thank you

It would be almost impossible to ascertain the number of ringers that have contributed to the collection of one of the world’s largest wader datasets, and to the scientific papers that have been published using WWRG data, but everyone that has been involved with WWRG over the past 60 years has played their part. Thank you to each and every one of the dedicated wader ringers that have made the past 60 years possible, worthwhile and fun.

For more history, read Clive Minton’s and Daphne Watson’s recollections of their early days ringing with the Wash Wader Ringing Group.

Discover what we have learnt over the past 60 years about the waders who use The Wash on this WaderTales blog, written by Group member Graham Appleton.

This page was written in 2019 to mark the Group’s 60th anniversary. It has been adapted from an article written by Allison Kew to mark the 40th anniversary, with more-recent content from the Group’s biennial reports.

Cover image: Setting a rocket net in 1962. Photo courtesy of Daphne Watson.