Curlew use the Wash both as a passage site to moult during autumn and as a wintering location. On a global scale, they are ‘Near Threatened’ i.e. vulnerable to extinction and they are present in Internationally important numbers on the Wash. Declines in the UK breeding population have placed Curlew in the highest category of UK bird conservation concern; therefore, the species is a priority for the group in terms of long-term conservation monitoring. We started to mark a proportion of the population on the eastern shore of the Wash with unique leg flags in 2012. This allows us to accurately determine their survival and assess wintering habitat use.

Since then, a total of 478 birds have been marked and we have had over 5,000 re-encounters recorded by over 200 WWRG volunteers and members of the public. We regularly dedicate fieldwork hours to ensure we have sufficient resightings to determine survival and winter distribution. This steady stream of data has started to be used in scientific publications to describe the east Wash Curlew population. This blog is a summary of what we have learnt so far.

Curlew are caught using cannon-nets during autumn passage when, on the highest tides, they roost inland on the eastern shore of the Wash. We started using white flags with two numbers and letters on the one leg combined with a plain ring on the other. More details available here: Current projects – Wash Wader Ringing Group (wwrg.org.uk)

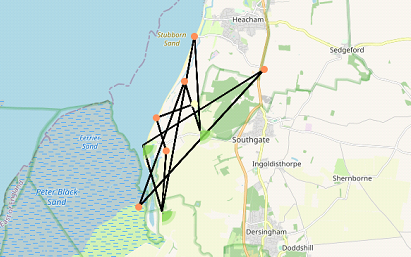

We increasingly spend time on our trips specifically looking for colour-flagged birds, and with around 15 miles of coast and the fact Curlew can forage in fields several miles inland, there is a lot of ground to cover! Despite this, the areas used by individual Curlew can be surprisingly small. We have found that the majority of captured birds stay close to where they were originally captured over winter. However, some birds disperse to wintering territories elsewhere within the study area, or to the nearby North Norfolk coast. Occasionally birds are reported even further afield, with wintering records from Kent and Cornwall.

Local habitat use

Somewhat to our surprise we have discovered that flagged Curlew use the coastal arable and pasture fields extensively over the course of winter. Some of these birds use these locations to supplement their food supply during high tide (when the intertidal feeding locations are covered by the sea) moving onto the intertidal as soon as it uncovers, others will roost during high tide without additional feeding. There are also some birds that feed inland and move back onto the estuary to roost late in the day. Curlew will roost on the beach during night-time high tides but use fields inland of the outer seawall to roost during daylight.

Survival analysis

The year-on-year re-encounter rates for flagged Curlew remain high, with over 90% of birds being seen in subsequent years. We now have sufficient data to calculate both passage and over-winter survival for Curlew on the Wash, with over 100 individuals encountered annually in both periods. Pooled analysis of survival modelling amongst Curlew around the UK, using both metal-ring data and flagged Curlew (Using data to make a difference – Wash Wader Ringing Group (wwrg.org.uk)) indicate that the survival of wintering Wash Curlew has increased in recent years (Cook et al 2021). This suggests that poor nest productivity is driving population decline, and there is little room to improve population size by improving winter survival; however, this does mean that increased threats to survival could spell disaster for the wintering Curlew population.

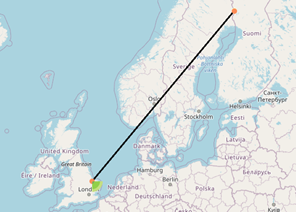

Overseas encounters

We know from metal-ringing data that most of ‘our’ Curlew breed in Sweden and Finland. Unsurprisingly, overseas re-encounters of ’our’ Curlew are on the Fennoscandian breeding grounds. The number of colour-flagged breeding birds reported abroad is already almost half of those that have ever been found bearing metal rings (26 vs 56 individuals); however, we have been undertaking metal ringing of birds for sixty years! In contrast, we have only a single flagged individual confirmed breeding in the UK. This indicates that Fennoscandian breeding birds account for the majority of birds wintering on the Wash.

Headstarting

The close monitoring of Curlew on the Wash has also allowed observations to be made of birds flagged as part of the recent multi-agency project to ‘headstart’ Curlew chicks from nesting attempts on airfields. (Released, captive reared Curlews phone home | BTO – British Trust for Ornithology). Headstarting involves raising chicks to independence in aviaries, so ensuring they are in good condition and reducing the large losses to predation over this period. Although the project is in the first season, we have seen several of these birds, including 4L who has spent the winter on the Wash.

Tagging wintering Curlew

Having found that birds vary in their use of wintering habitats (with more use of inland feeding locations than anticipated), during 2021, 10 birds were fitted with tags that download data to the mobile phone network. This is allowing us to study the winter movements of individual Curlew at a greater level of detail than is possible with leg flag resighting and we will also be able to find out if ‘our’ Curlew tend to migrate in one direct trip or use stopover sites.

World’s best studied Curlew population?

The Wash passage and wintering population have ecological data generated by flag resighting, long term (60 years plus) metal-ringing data, and movement analysis by tagging. This makes the Wash Curlew population dataset one of the most comprehensive in the world. We anticipate more work contributing to our understanding of habitat requirements for wintering Curlew to be undertaken over the next 10 years and look forward to contributing to the survival of this charismatic, yet threatened, wader species.

Reference

Cook, A.S.C.P., Burton, N.H.K., Dodd, S.G., Foster, S., Pell, R.J., Ward, R.M., Wright, L.J. & , Robinson, R.A. (2021) Temperature and density influence survival in a rapidly declining migratory shorebird. Biological Conservation 260, 109198.

Blog written by Rob Pell