Birth, and copulation, and death.

That’s all the facts when you come to brass tacks:

Birth, and copulation, and death.

I’ve been born, and once is enough.

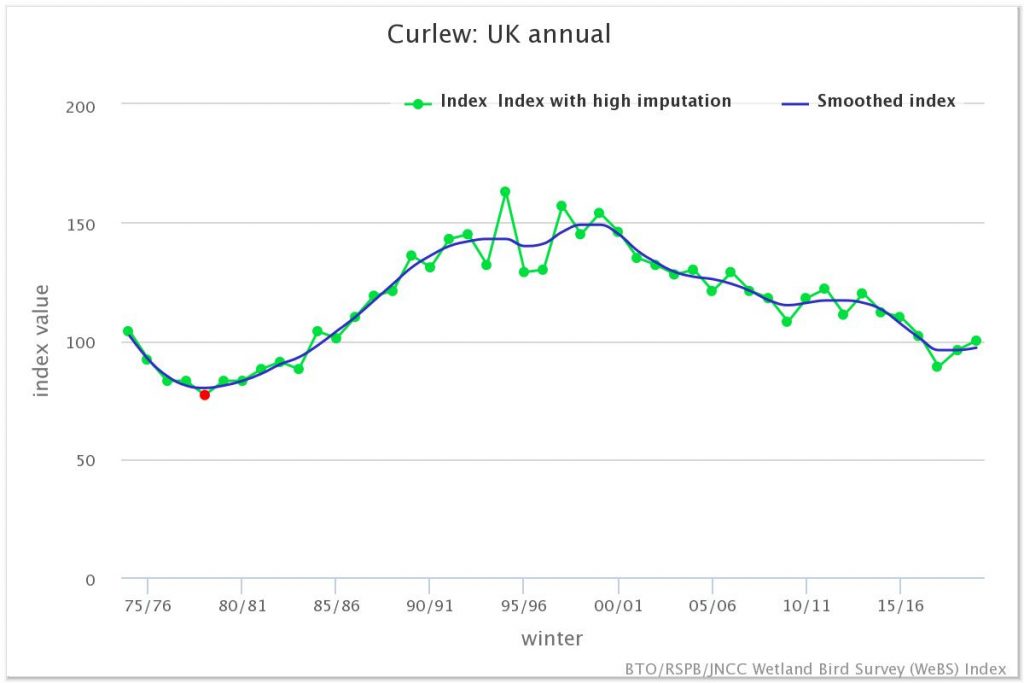

Although not involved in bird study, these lines from T. S. Eliot encapsulate our current studies of wader populations on The Wash. Bird populations are sustained by recruitment of fledged young into the adult population at an equal rate to the death of individual adults. More recruitment than deaths equals more birds. Unfortunately, the opposite is currently occurring in Eurasian Curlew, which is experiencing population decline. This could be due to not enough chicks being raised to adulthood from each nesting attempt, or alternatively, it could be due to increased death of adult birds. Knowing which factor is more important allows conservation efforts to be prioritised: do we need to protect Curlew nests to improve chick survival or do we need to enhance protection of wintering Curlew to improve adult survival? A recently published paper has explored one part of the equation – survival in Curlew – using data from The Wash, as well as other wader ringers around Britain and Ireland.

Understanding what is driving population decline sounds simple, but like many things in life it becomes more complicated the more you think about it. We need to look at how successful Curlew are at nesting and hatching chicks that go on to join the adult population. We need to look at how successful adult Curlew are at surviving year on year. We need to look at Curlew that both breed and winter here, and those that winter in Britain but breed in other countries (as movement into and out of a population also affects population size). We need to repeat this measurement for multiple wintering sites (as survival can be dependent on things like the quality of the feeding or the availability of safe roosts on a particular site). We need to repeat the observation for multiple years, in case a really bad winter affects survival. We need to look at lots of birds, because the sample size needs to be big enough for any observation to not be just due to chance.

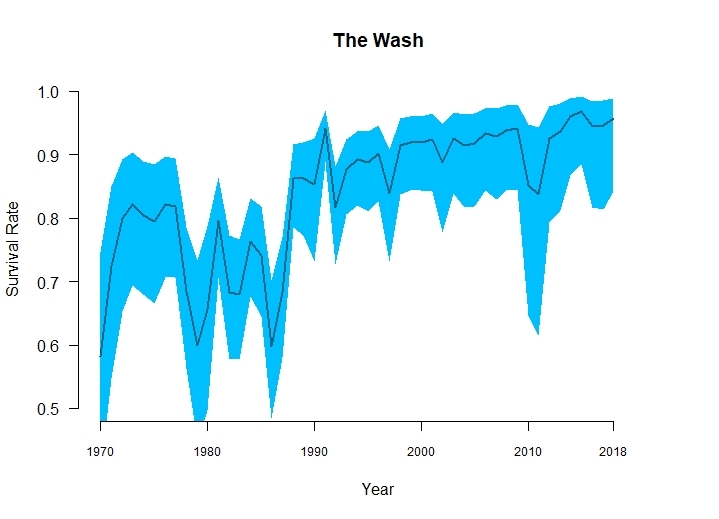

To answer the original question, we need to be able to incorporate all these factors into a mathematical model. And the mathematical model needs data. Lots of data. All the ringing data and nesting outcomes available on Curlew submitted to the BTO over a period of fifty years in fact! Thankfully, due to the dedicated work of the Wash Wader Ringing Group we have been able to amass over fifty years of ringing and flag resighting data on Curlew. This was combined with four other datasets from wintering sites, plus records of Curlews ringed as chicks, to look at Curlew survival over time.

Comparing both British and overseas wintering populations indicates there is little room to change population size by increasing adult survival. Curlew have amongst the highest year-on-year survival rate of any wader (over 90%) and this has been increasing on The Wash in recent years. Once we know the adult annual survival rate (and the survival rate of newly recruited young, fledged Curlew), we can work out how many chicks need to be generated from each nesting attempt to sustain the population. To achieve a stable population size, around 0.43 chicks need to be generated from each nesting attempt. This is an issue, as only 0.25 chicks are currently generated from each nesting attempt, which explains the source of the problem surrounding Curlew population declines.

So, to stop Curlew populations declining, we need to prioritise ensuring more nests successfully result in fledged young Curlew. BUT – we also need to make sure that nothing happens to reduce survival in the adult population, by continuing to protect their wintering habitat. Ensuring adult Curlew are in optimal health at the end of winter so they can successfully migrate and breed is also important, as this improves the likelihood of reproductive success (and more chicks!).

This paper, by BTO staff, members of the Wash Wader Ringing Group and wader ringers elsewhere in the UK, demonstrates how our ringing efforts are translated into a larger picture of how wader populations work. Knowing more about the drivers of population change through ringing allows targeted conservation efforts to be planned and carried out to benefit waders around the world.

Thank you to all WWRG volunteers who have helped to collect Curlew data over the years, with particular thanks to those who have spent so many hours searching for and reporting flagged birds.

Blog written by Rob Pell